|

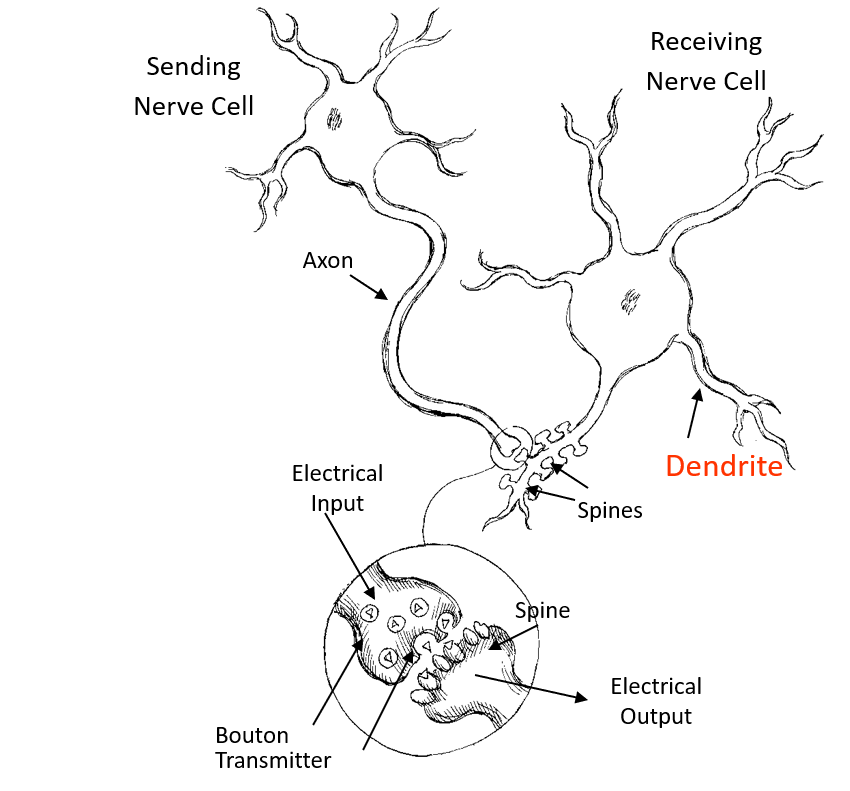

Since 1734 when Christian von Wolff came up with the theory that the human mind is a separate entity than the rest of the body (see Faculty Psychology here), the education of American students — as well as students in other parts of the world — has been to exercise and strengthen the intellect of students through the educational model called “mental discipline.” For younger students this meant the tedious drill and repetition of basic skills. For older students this meant the eventual study of abstract subjects such as classical philosophy, literature, and languages. While additional subjects like history, geography, and science have been added to what children are supposed to learn, many methods and even text books have remained the same. Noah Webster’s “American Spelling Book” (first published in 1783) and William Holmes’ “McGuffey Readers” (first published in 1836) are still in print and used by some educators today. By 1906, the Carnegie Unit was adopted as the way to assure students received a an adequate education. Students are awarded credits for classes based only on seat-time (how much time the student spends in class). Carnegie Units are still used today to determine the credits necessary to graduate from high school or other accredited institutions. While some things have changed in the last nearly 300 years, unfortunately in the case of educating children much has stayed the same despite modern research into how the brain learns best, even among children who are educated at home. Why? That’s not a debate I’m ready to tackle. :) But how can we better teach our children? That one is easy. First, we need to make learning fun. Emotion is like an on/off switch for learning. Dr. Robert Sylwester said, “Emotion drives attention & attention drives learning, memory, problem solving, & just about everything else.” Our children need to have a positive reaction to what they are learning or their brains turn off. If all they are exposed to are worksheets, textbooks, quizzes, tests, and abstract learning, their brains will remember only that the content being taught to them is boring and not worth remembering beyond the test. Second, we need to realize that stress can cause our brains to shut down. Some educators try to reduce stresses in the classroom by using a philosophy called “Absence of Threat.” What this really means is a classroom free of stress — both real or imagined. All students should feel safe to learn, explore, share, and even exist within a culture of respect. If our students are stressed they cannot learn. This is equally true in the home. The more a child feels accepted, valued, and respected, the more teachable they are. Third, fibers called dendrites grow from your neurons. Each neuron (our brains have at least 100 billion of them!) is capable of growing 10,000 or more dendrites. As you learn new things, new dendrites are formed. New dendrites can also grow from existing dendrites, similar to the way twigs sprout from the branches of trees, when you learn things that are connected or in a pattern. Your dendrites can connect with other dendrites to cause something called synapse when you learn things that are connected. Your neurological network grows stronger and stronger the more you learn. However, if the things you learn about are not part of a pattern, your dendrites may grow on neurons that are not connected. Those dendrites run the risk of getting weaker or shriveling. The same thing can happen if you stop learning. It then becomes harder to retrieve that information. We need to understand that our brains are able to change — for better or worse — at any age. The technical term for this is “neuroplasticity.” Our brains are full of cells called “neurons” which are capable of forming new connections or reorganizing old ones in response to changes in our environment or to adapt to new situations. By providing an environment that is conducive to learning, we give children a better chance at building new connections or strengthening old ones.

Our brains are pattern-seeking devices. To take advantage of that, parents should ascertain what each child knows so they can build upon that existing knowledge. They should then present new information in a way that relates to what the student already knows. This gives children the opportunity to strengthen dendrites already existing and to grow new ones, enabling the child to come up with answers more quickly. While there are many other ways to take advantage of current brain research when teaching our children, these three can start helping you make a difference in your homes. To receive a FREE 10 point guide on teaching in a brain-compatible way, click here.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed